‘Mr. Mozart’ finishes comprehensive catalog of maestro’s work | Cornell Chronicle

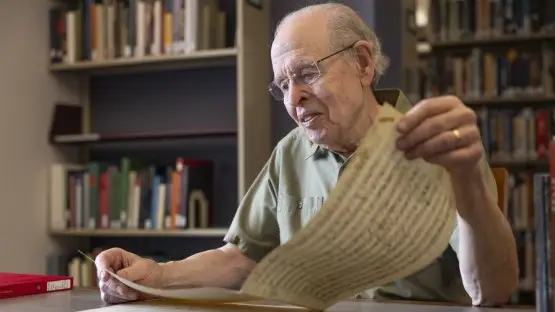

Acknowledgment: Ryan Young/Cornell University

For thirty years, Zaslaw worked meticulously to create an extensive collection of over 600 works by Mozart.

How does someone achieve the title of "Mr. Mozart"? Just like a captivating symphony, Zaslaw’s musical journey has had many different phases. He started off as a flutist with formal training, attending the Juilliard School and playing with the American Symphony Orchestra directed by Leopold Stokowski from 1962 to 1965. In addition to his musical pursuits, he obtained a Bachelor’s degree from Harvard and went on to earn graduate degrees from Columbia University.

While pursuing his doctoral studies, Zaslaw thought about focusing on Mozart for his dissertation. However, his advisor, the esteemed musicologist and critic Paul Henry Lang, had some reservations regarding that choice.

He appeared worried and remarked, "This is a vast topic, and a lot of work has already been accomplished." Lang was acquainted with his contemporaries, who had achieved significant milestones, and he felt they had managed it quite effectively. He mentioned, "I wouldn't recommend that a recent graduate in musicology dive into a project of this magnitude." Zaslaw added, "This was genuinely heartfelt guidance from a seasoned academic." So, I decided to focus on a different subject instead.

When Zaslaw joined Cornell in 1970 and was asked about the type of research seminar he wished to conduct, he immediately thought of Mozart. He quickly realized that there was a lot of excitement happening in the field of Mozart studies. Scholars in Salzburg were working on a new edition of the composer's works, uncovering new sources of information in the process. Additionally, new methods had been developed to reassess the dating, context, and authenticity of Mozart's music.

In reality, there was much more to discuss, and Zaslaw’s experience in both performance and academia gave him the perfect qualifications to tackle the subject.

Zaslaw shared, “Having undergone extensive professional training both as a performer and an academic, a significant part of my life has focused on connecting these two worlds. For 50 years at Cornell, I guided my students to integrate these aspects—helping performers develop their scholarly skills and encouraging musicologists to engage in performance. Without this blending, they would lack essential insights that are vital to their understanding and conclusions.”

Zaslaw is an accomplished author and editor, having produced many books and over 75 articles focused on baroque and classical music, performance practices from history, the evolution of orchestras, and the works of Mozart. He served as the chief editor for Current Musicology and handled book reviews for Notes, which is the official journal of the Music Library Association. From 1978 to 1982, he acted as a musicological consultant for Decca Records' Oiseau-Lyre label, overseeing the recording of all of Mozart's symphonies (around 60) performed by the Academy of Ancient Music and conducted by Jaap Schroeder and Christopher Hogwood.

In 1991, he was honored with a knighthood by the Austrian government in recognition of his work in performing and studying Mozart's music. This is how he came to be known as "Sir Mr. Mozart." However, Zaslaw emphasizes that his musical tastes are broad, spanning from ancient Greek compositions to contemporary electronic music. As a musician, he had a special appreciation for Mozart's flute compositions and admired the way the composer fused traditional elements with innovation, mixing the unusual and the rational.

"He appeared to play for both teams," he remarked. "And for some reason, that brought me joy."

When the agreement for the new Köchel catalog was finalized in 1993, Zaslaw and the publisher settled on a sensible timeline.

"The agreement stated that I would complete it in seven years," Zaslaw mentioned. "As the years turned into decades, I continued to enjoy it, but I started to question whether I would be able to finish it before my time was up."

"It’s an incredible sense of relief."

As Zaslaw delved into the project, the Cold War was still ongoing, and collaboration between libraries and archives from the capitalist and communist worlds was limited. However, there had been some advancements. After years of speculation, the Russians confirmed in 1976 that the manuscripts removed from the Berlin library were kept in the basement of the University of Krakow's library in Poland. In the spring of 1977, Zaslaw traveled to Krakow to inspect the manuscripts, meticulously taking notes.

However, Zaslaw faced a bigger problem with the catalog, one that earlier Köchel editors had failed to solve. The ingenious classification system created by Köchel was breaking down due to its inconsistencies.

The original catalog listed Mozart's compositions in the order they were created, but this approach became complicated over time because of recent findings, revisions, and, interestingly enough, Mozart's own process of working, which was more step-by-step than planned out. This way of working challenges the idealized image that many of his fans have of him.

In the common view of Viennese classical composers, Zaslaw described Haydn as the refined traditionalist whose music seemed reminiscent of the powdered wigs of his time. Beethoven was seen as the passionate rebel, while Mozart was regarded as the extraordinary talent whose creations appeared to be touched by divine inspiration.

Geniuses who are inspired by a higher power don't go back to edit their creations.

According to Zaslaw, Mozart was an incredibly dedicated and productive composer. When he passed away in 1791, he had left behind a vast collection of written works and music scores that were found all over Western Europe.

"This is a complex issue, as it relates to a conflict between cultures and the idealized vision of a genius," he explained. "The reality is that many of Mozart's compositions come in various forms. While he worked, he would often modify pieces for different contexts, whether in different venues with unique acoustics, with various solo performers, or depending on the support he received. This left the Germans and Austrians in a difficult position of having to determine which version was the true masterpiece. So, I thought it was important to delve into all of that."

Zaslaw was able to access numerous fresh resources that earlier Köchel editors did not have at their disposal. These included the internet, a new wave of scholars eager to collaborate and share knowledge, and global initiatives focused on cataloging libraries and archives that had never been thoroughly organized.

However, there was one more remnant of tradition that posed a challenge for Zaslaw: the Köchel legacy itself.

"I spoke with numerous performers, librarians, archivists, scholars, and publishers," he explained. "They all told me the same thing: ‘You can’t alter the numbering system used for Mozart’s compositions. For instance, his G minor symphony is listed as K. 550 in the Köchel catalog. Assigning a different number to it would lead to confusion.’"

Zaslaw devised a clever but labor-intensive approach to the project. He kept the old numbering system, but removed the word "chronological" from the book's title. Additionally, he created a detailed new indexing method to give proper credit to his sources. Once he completed the catalog, he shared it with specialists at the Mozarteum, a comprehensive institution in Salzburg that includes a concert hall, music school, university, three museums, and a library, archive, and research center. They offered their insights, translated the book into German, and took care of its formatting.

After a wait of 24 years since it was first announced, Zaslaw’s Köchel has finally been released, bringing him “incredible relief,” as he expressed. This substantial volume spans around 1,300 pages and marks the fifth official Köchel edition, likely the last one. In the future, the catalog will transition to an online format, allowing for easy updates, notes, and corrections to be made instantly.

"While Neal might see this publication as an incredible sense of relief, for the rest of us, it’s simply amazing," remarked Benjamin Piekut, a music professor and department chair at the College of Arts and Sciences. "It's rare for any project to take thirty years, but this one did. It truly reflects Neal’s remarkable standing as a teacher, as countless generations of musicology doctoral students have had the chance to collaborate with him on this project during seminars throughout the years."

Zaslaw is set to head to Salzburg for the release of his book. The event will take place at the Mozarteum and will align with a weekend conference focused on the composer. He'll be joined by his wife, psychologist Ellen Zaslaw, as well as their two daughters.

Zaslaw shared that he was both moved and surprised that his extremely busy daughters decided to pause their hectic careers in Atlanta and San Francisco to visit him and their mother in Salzburg. Their reply was, "You might have thought you only had two kids, but we always saw you as having three. There was also that other guy known as Mozart."