Intel Co-Founder and Creator of Moore’s Law, Gordon E. Moore, Passes Away at 94.

In the 1960s, he foresaw that there would be significant developments in computer chip technology, which paved the way for the era of advanced technology.

The blog post was released on March 24, 2023 but it underwent an update on March 25, 2023 at around 3:26 in the morning Eastern Time.

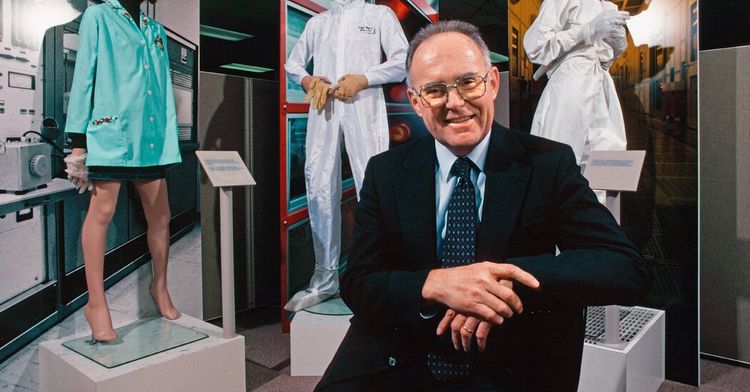

Gordon E. Moore, one of the founders and previous chairperson of Intel Corporation, which is a company located in California that produces semiconductor chips that played a significant role in the development of the Silicon Valley, passed away on Friday at his residence in Hawaii. He was 94 years of age. Intel Corporation was able to achieve an immense amount of power that was once held by the massive American steel or rail companies of the past.

Intel and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation have announced that he has passed away. However, they have not revealed the cause of his death.

Mr. Moore, along with a small group of coworkers, can be recognized for introducing laptop computers to countless individuals and integrating microprocessors into a variety of devices including scales, toasters, toy fire engines, as well as phones, cars, and airplanes.

Mr. Moore always dreamed of being a teacher, but unfortunately, he couldn't land a job in the education sector. Unexpectedly, he ventured into entrepreneurship, earning his nickname "the Accidental Entrepreneur." He invested only $500 in the emerging microchip industry, which eventually transformed electronics into a colossal global market, allowing him to accumulate a fortune worth billions.

According to his coworkers, he was the one with the vision. Back in 1965, he made a prediction known as Moore's Law, in which he foresaw that the amount of transistors that could fit onto a silicon chip would grow exponentially with regular intervals. This, in turn, would lead to a significant increase in the processing power of computers.

Later, he included two additional principles: As technology advances, producing computers will become progressively more costly. However, as a result of the large number of units sold, customers will be charged less and less for them. Moore's Law was validated for many years.

By combining their brilliance, leadership skills, charm and network, Mr. Moore and his partner, Robert Noyce, managed to gather a team of highly skilled technicians who are often recognized as some of the most daring and innovative in the world of technology.

This team suggested using super-thin silicon chips, which are made from a sand-like material that has been treated with chemicals. Silicon is a widely available natural resource that proved to be extremely effective at holding intricate electronic circuits with faster processing capabilities.

In the mid-1980s, American manufacturers were able to surpass their Japanese competitors in the computer data-processing field thanks to Intel's silicon microprocessors, which serve as the computer's brain. By the 1990s, Intel had secured its position as the most successful semiconductor company in history, as its microprocessors made up 80% of all computers being produced globally.

Most of these events occurred during the time Mr. Moore was in charge. He held the position of CEO from 1975 until 1987, at which point Andrew Grove took over, and Mr. Moore stayed on as chairman until 1997.

As he accumulated more riches, Mr. Moore also became a significant player in charitable works. He established the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation in 2001 with a gift of 175 million Intel shares, and along with his wife, they bestowed $600 million to California Institute of Technology, which was the most sizable individual endowment granted to a higher education institution at the time. At present, the foundation holds assets valued at more than $8 billion and has dispensed over $5 billion in contributions since its inception.

During interviews, Mr. Moore usually downplayed his accomplishments, especially the technological innovations that made Moore's Law feasible.

During an interview with Michael Malone in 2000, the speaker shared his belief that semiconductor devices would play a significant role in reducing the cost of electronics. He aimed to convey this message to others. In retrospect, he was surprised to discover that his prediction was more accurate than he initially anticipated.

Mr. Moore had foretold that electronics would become less expensive as the industry moved from discrete transistors and tubes to silicon microchips. His prediction turned out to be so dependable that technology corporations made their product plans based on the belief that Moore's Law would remain valid.

Harry Saal, a well-known businessperson in Silicon Valley, stated that businesses that did not factor in this level of transformation in their multi-year planning would likely be left behind.

Arthur Rock, a pal of Mr. Moore's who invested in Intel at the start, declared that the thing Mr. Moore will be most well-known for is "Moore's Law," not his involvement with Intel or the Moore Foundation.

Gordon Earl Moore was born in San Francisco on January 3rd, 1929. He spent his childhood in Pescadero, a small town located south of San Francisco. His father, Walter H. Moore, served as the deputy sheriff, while his mother, Florence Almira Williamson, belonged to a family that managed the town's general store.

Mr. Moore signed up for San José State University (previously known as San Jose State College) and there he crossed paths with Betty Whitaker, who was studying journalism. They tied the knot in 1950. The same year, he finished his bachelor's studies in chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley. Four years later, he earned his PhD in chemistry from Caltech.

When he was beginning his career, he submitted an application to work as a manager at Dow Chemical. As part of the process, he met with a psychologist to assess his suitability for the role. According to Mr. Moore's 1994 writings, the psychologist concluded that he possessed adequate technical skills, but wasn't capable of effectively overseeing any kind of operation.

Mr. Moore got a job at the Applied Physics Laboratory located in Maryland at Johns Hopkins University. After that, he tried to find a way back to California and went to an interview at the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, located in Livermore, Calif. Although they offered him a job, he chose not to accept it because of the nature of the work. He went on to explain in his writing that he didn't want to take spectra of exploding nuclear bombs and decided against it.

Instead of doing something else, Mr. Moore started working with William Shockley, who had invented the transistor, at a division of Bell Laboratories on the West Coast in 1956. Their goal was to develop an inexpensive silicon transistor.

Shockley Semiconductor failed because Mr. Shockley did not know how to manage a company. In 1957, Mr. Moore and Mr. Noyce left with a group of others who became known as "the traitorous eight." They each contributed $500 and were backed by $1.3 million from Sherman Fairchild, an innovator in aircraft. They formed the Fairchild Semiconductor Corporation, which was one of the first companies to produce integrated circuits.

Captivated by the entrepreneurial spirit, Mr. Moore and Mr. Noyce made the decision to establish their own business in 1968, with a primary focus on semiconductor memory. They crafted a basic business plan which Mr. Moore characterized as "abstract."

During a 1994 interview, he stated that the plans involved utilizing silicon in the creation of captivating merchandise.

Despite their unclear plan, they easily secured funding.

Mr. Moore and Mr. Noyce named their start-up "Integrated Electronics Corporation" and abbreviated it to "Intel". They had $2.5 million in capital. The third individual they hired was Mr. Grove, a young immigrant from Hungary who had previously been employed by Mr. Moore at Fairchild.

The three men were uncertain about which technology to prioritize. Eventually, they agreed to work on a latest variant of MOS, which is short for metal oxide semiconductor. This version makes use of silicon-gate MOS technology, utilizing silicon instead of aluminum to increase the transistor's speed and density.

Thankfully, through sheer chance, we stumbled upon a technology that presented just the appropriate level of challenge for a prosperous business launch," stated Mr. Moore in 1994, "This is how Intel came to be."

During the beginning of the 1970s, the introduction of Intel's 4000 series "computer on a chip" initiated a significant change in personal computers. However, Intel failed to take advantage of manufacturing a PC, which was partly due to Mr. Moore's lack of foresight according to his own admission.

Many years ago, an engineer working for us proposed an idea that Intel should create a computer specifically for personal use. The big question was, “Why on earth would anyone want a computer in their own house?”

Despite everything at the time, he had a vision for what was to come. As the director of research and development at Fairchild in 1963, Mr. Moore wrote a book chapter outlining what would later become known as his famous law, but without giving any specific numerical predictions. Just two years afterwards, he wrote an article for the popular trade magazine, Electronics, titled "Cramming More Components Onto Integrated Circuits."

David Brock, who co-authored the book "Moore's Law: The Life of Gordon Moore, Silicon Valley's Quiet Revolutionary," stated that the article made the same argument as the book chapter but included an explicitly numerical prediction.

According to Mr. Brock, there isn't much proof that a lot of individuals perused the article at the time of its publication.

According to Mr. Brock, the speaker continued to present lectures that included charts and diagrams. Eventually, others began utilizing and replicating his presentations. As a result, individuals began to take notice of this occurrence. They observed that as silicon microchips became more intricate, the cost of manufacturing them went down.

During the 1960s, Mr. Moore started his career in electronics. At that time, a silicon transistor could be purchased for $150. As time passed, $10 was enough to obtain over 100 million transistors. Mr. Moore expressed his belief that if cars had progressed as rapidly as computers, they would have been able to travel up to 100,000 miles with just one gallon of fuel. Additionally, owning a Rolls-Royce could have been cheaper than parking it. However, in this scenario, cars would have been just half an inch long!

Mr. Moore is survived by his spouse, along with his two sons, Kenneth and Steven. Additionally, he has four grandchildren.

According to Forbes in 2014, the net worth of Mr. Moore was valued at $7 billion. Nonetheless, he did not feel the need to show off his wealth and preferred casual wear like tattered shirts and khakis instead of expensive tailored suits. He was a regular shopper at Costco and even kept things like fly lures and fishing reels on his desk at work.

The end of Moore's Law is inevitable, as engineers face certain physical restrictions and the exorbitant expenses involved in constructing the necessary factories for further miniaturization. Additionally, there has been a noticeable deceleration in the rate of miniaturization in recent times.

Every now and then, Mr. Moore expressed his thoughts about the unavoidable termination of Moore's Law. Back in 2005, during an interview with Techworld magazine, he stated, "It's impossible to carry on forever. Exponentials work that way, where you keep pushing them out until things catastrophically go wrong."

In the year 2017, Holcomb B. Noble, who previously held the role of science editor at The Times, passed away.